When we went to Ísafjörður in the fall of 2020, we stumbled across a humongous driftwood log in front of the Westfjords Heritage Museum. As its roots were intact, it must have eroded naturally. The museum guide told us: “I have no idea where it came from – one morning it was suddenly just there”. We started asking around and it turned out that Kristín Ósk Jónasdóttir – advisor for the nature reserve Hornstrandir, was on the Coast Guard ship Thor, when they found it at sea in June and took it on board to prevent danger from smaller boats. Kristín however, did not know what happened to the log afterwards. Finally the seller at the fish shop told us it belongs to Maggi, the chef of the restaurant Tjöruhúsið, next to the museum. So we went to talk to him, he said he had never seen a log this huge and that it was sitting at the harbor one day and as no one else claimed it, he did. It took a crane to move it and Maggi estimated it weighed about 3,5 tons. Where exactly was the log found? How old might this tree be? Where did it originate from? And when did it erode from a river bench? We started to research.

The Icelandic Coast Guards wrote:

“According to the ship’s log onboard the ICG vessel Thor, the large driftwood was picked up on 17th June 2020 at 18:15 in pos. 65°06,3´N-023°39,1´W or approx. 12.4 NM north of Ólafsvík.

The driftwood was put ashore at Ísafjörður on 21st June at 08:54 according to the ships log.”

Driftwood Log

Ólafur Eggertsson from the Icelandic Forest Service, offered to take samples to see if he could find out more about the driftwood log.

Step 1: Measure the Driftwood Log

Length: 13,10m

Circumference: 2,23m

Step 2: Take Core Samples

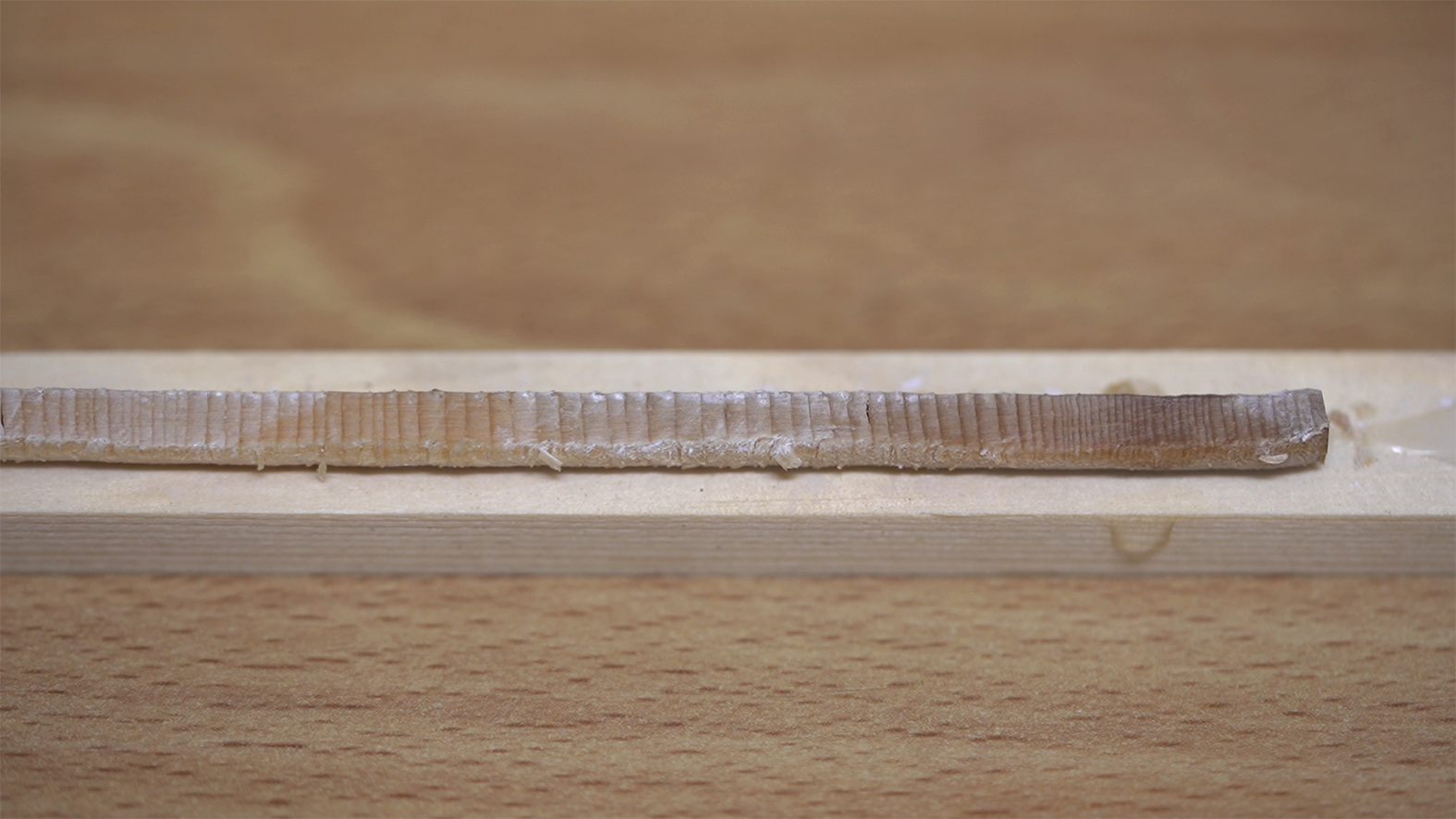

Ólafur takes samples from different spots of the log, in order to possibly catch every year of the tree’s life. A classic spot for a core sample is at breast height (“tree hugging height”) at 1,30m.

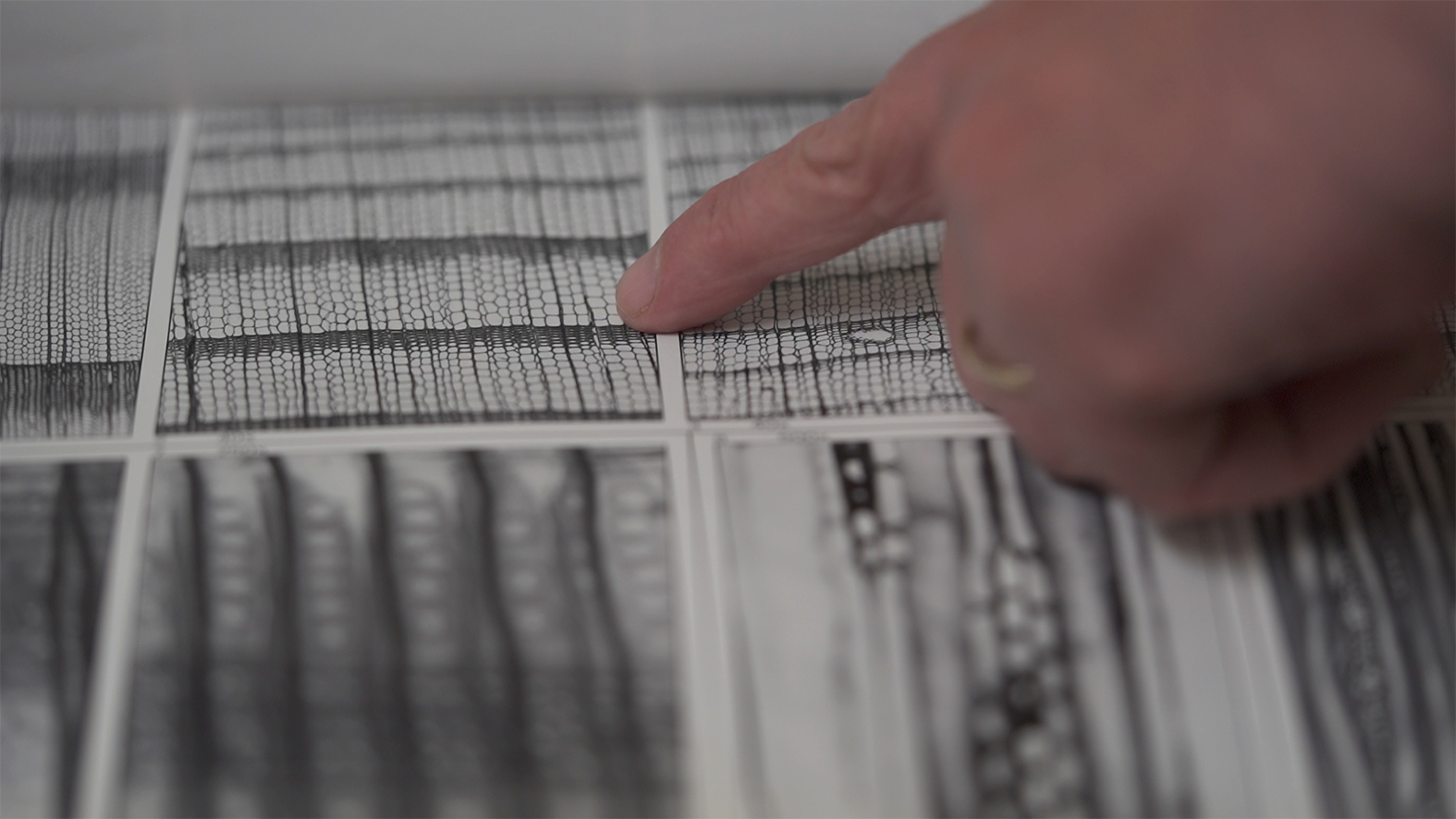

Step 3: Study the Wood Anatomy

Ólafur glues each tree ring sample on a pin and from one of them, he cuts a very thin slide which he puts under the microscope. Each tree species has a distinct cell structure and Ólafur compares its features with reference samples. “The first thing you see is if it’s a coniferous or a broadleaf wood, as the cell structure of coniferous wood is much more simplified,” he explains. “The only problem is that the wood anatomy of spruce and larch driftwood is quite similar, so we have to find one specific feature that helps us to differentiate.” As our log samples don’t have a reddish color and the borders between the tree ring’s early and late wood are not very distinct, Ólafur can identify the species of our log as Norway spruce. The species gives us already a rough idea about the tree’s origin as their range is known. Larch driftwood for example mainly originates in Russia, while aspen is very common in Alaska and Canada. The range of spruce however, is extremely wide so our log could originate from Russia, Alaska or Canada.

Step 4: Study the Tree Ring Widths

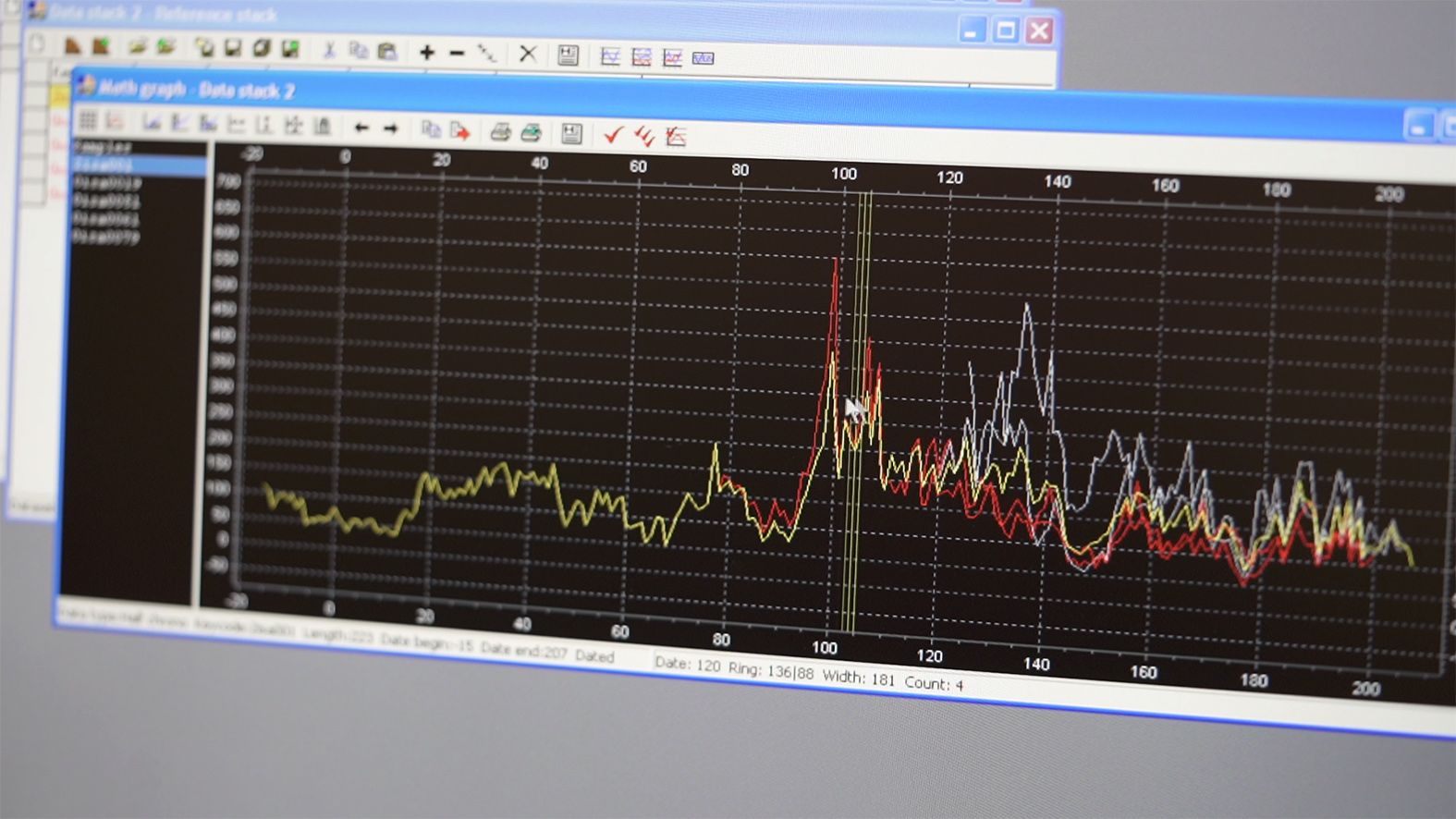

Ólafur cleans up the samples to make the tree rings more visible and puts them under a microscope which allows him to count and measure the width of each tree ring. The outermost tree rings are grey because the salt water from the ocean penetrated the driftwood during its long journey. Ólafur starts with the innermost – or oldest – tree ring and the width of each tree ring shows up on his screen, creating a chart. “We are recording the history of the tree growth and at the end we can count the tree rings and can find out how old the tree is,” Ólafur says. Wide rings reflect warm summers, narrow rings cold summer temperatures – but there are also other local factors like insect attacks that determine the width of a tree ring. To study the climate history of a whole forest, it’s therefore necessary to take many samples from the same forest in order to find out the average tree ring widths. Ólafur completes his measurements and the graph now shows the history of our driftwood log.

The graph covers 215 years and our spruce could be even older than that as the inner part of the tree was rotten next to the root. The tree ring widths for the first 30 years in the tree’s life are very narrow, reflecting growth in a dense forest with little sunlight. After that, the tree might have gotten more sunlight and it grew faster and stable for the next 50 years. The graph shows a disturbance after 80 years where the tree started to increase growth and after 120 where the tree rings become even wider. After that, the tree went back to normal growth. “And then suddenly something happened and it fell into the river,” Ólafur states. The tree didn’t die during winter, he explains: “One sample shows a fully formed tree ring first, but the next ring only contains about 10 new cells of wood – so the tree had just started to grow a new ring in early summer, right before it died. When you measure naturally eroded driftwood logs, you can often see the disturbance starting a couple of years before they fall into the river, because they are tilting. But this log doesn’t show these features, so it fell quite abrupt. It was growing nicely, probably in a sort of clearing as the rings are wide and then some event like a flooding caused by an ice dam breach, provoked it to fall into the river.”

Step 5: Crossdate our Tree Ring Chronology

From our graph that includes the tree ring widths of all the samples we took from the log, Ólafur creates another graph showing the average growth history of our tree. He tries to crossdate our sample with existing tree ring chronologies from Alaska, Canada, Norway and Russia – but he doesn’t find a match. “This log is like a fingerprint and we have this databank of fingerprints of all around the Arctic, but we did not find our log’s origin. It’s still a mystery when and where this tree fell into the river. Sometimes it’s hard to successfully crossdate a tree ring pattern if you just have one driftwood log.” When he sees the look on our faces, he tries to cheer us up: “But this log has more than 200 tree rings so it still might be possible to find out its origin.” (tbc)