isn't trash just trash? It's not!

Interview with Catherine Chambers, University Centre of the WestfjordsHow would you compare the floating habits of driftwood and plastics?

Plastic floats differently than driftwood. We think that it has a lot to do with the way the wind is moving rather than the general currents because plastic is probably floating in the top five layers of the ocean. But this could also apply for smaller pieces of driftwood. In 2019, a working group of the Arctic Council launched a “plastic in a bottle” in Iceland that was equipped with a GPS tracker – within seven months, it travelled 7.000 kilometers to Greenland and towards Newfoundland before heading east and being washed ashore on the Scottish island Tiree.

During beach clean-ups, do you find plastic that you can trace back to its origin and also find out when it got lost?

On Icelandic beaches up in Hornstrandir or on our beach clean-up strip on the eastern side of the Westfjords we have found lobster tags from Nova Scotia, Canada. Lobster fishermen tag each lobster pot individually, so if the pot gets lost and the tag becomes free we know almost essentially what day it came free and started traveling around the ocean. We assume that this plastic material floats with the Gulf Stream and North Atlantic Current from Nova Scotia towards Ireland and then with the Irminger Current north towards Iceland.

Due to the directions the wind blows, the plastic could potentially also float from Nova Scotia north into Baffin Sea and circle clockwise around Greenland – this is feasible, but we’re actually not sure if this is of how the majority of plastic or anything that drifts would be coming to Iceland. But from the lobster tags we know that plastic can take just about two years to get from Nova Scotia to Iceland and up into Svalbard. That’s really fast!

What thoughts cross your mind during a beach clean-up?

In a way, beach clean-ups are like treasure hunting where you’re trying to find out where stuff comes from. You’re picking up Russian vodka bottles made of glass or shampoo with French writing and you might ask: Does that really matter, isn’t plastic just plastic, isn’t trash just trash? It’s not! All these things that are floating tell a story like driftwood tells a story, everything comes from somewhere and has human activity inscribed in it. There’s more plastic now than there was, it used to be mainly driftwood that was floating around. But all of these things connect us across the ocean and across the globe. I would like to meet the lobster fisherman who lost his pot in Nova Scotia and the loggers who lost their wood in Siberia. I’ve always been curious if the people who lost the driftwood are aware that it comes to Iceland and is an important part of the culture here. When you think about marine resources and Iceland you always think about fish but although driftwood is not a big money maker it is inscribed in the daily activities of people in this area – and that means that it’s important

We were told that last winter a lot of new driftwood along with very old plastic bottles washed ashore – what do you make of this companionship?

One thought is that we got this big pulse of driftwood and plastics because they were frozen in sea ice and then it melted or a big storm broke up part of the ice. Some of the old fishing nets we’ve seen have been at the sea maybe since the 50’s or 60’s and some things are much older than that. It’s hard to date them and to really understand where they came from. But I do think that climate change impacts the way that things that are adrift reach Iceland due to changing sea ice patterns, changing weather conditions as well as the increased frequency of storms.

How do you detect the age of plastic?

We’re looking for expiration dates which give us an idea when a toothpaste or a bottle was manufactured and how long it was at sea. When things are degraded that of course means they’ve been at sea for a while. For some fishing gear, you can tell when they went into the ocean because of changing regulations of mesh size for example, there will be times when they would have been banned, in other words a date past which they would not have been used. We know that some gear was used a lot in the 70’s or 80’s and then a new rule came and the mesh or net size changed.

A really common find on the beaches are shotgun shells from seabird hunting and cross shaped parts of larger trawl nets. They’ve cut them before the knots because something would have been broken that they needed to mend. The cross shaped part gets thrown on the deck of the ship because you’re working so fast and then it eventually gets washed into the ocean. Most of the stuff we find is related to the fisheries, even the strange amounts of boots at the beaches. We’re also looking at the life that grows in the plastic, trying to find out if plastic can be a vehicle for invasive species.

How do you sort the trash you find at beach clean-ups?

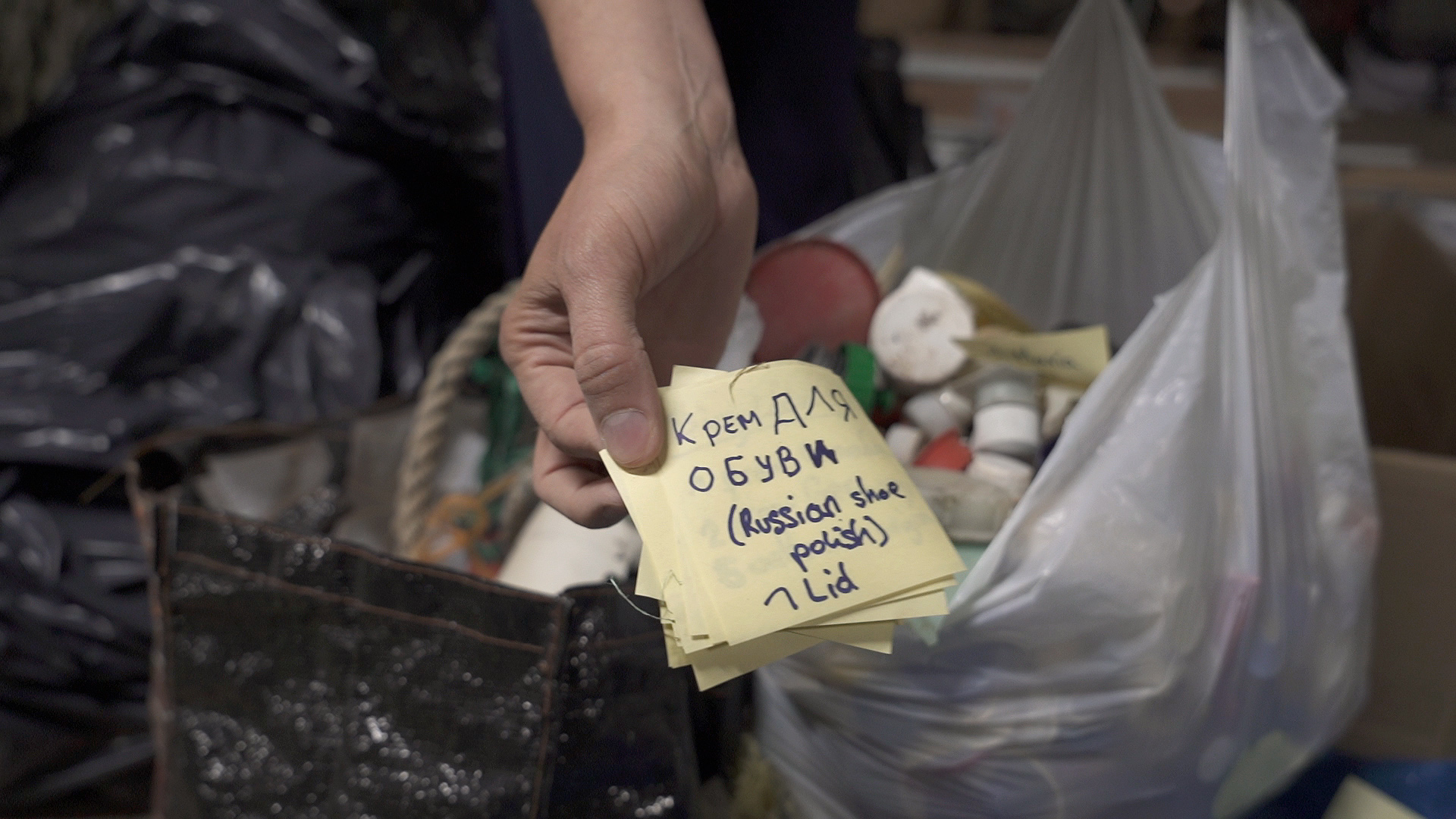

We categorize the plastic we find either based on the number of items or by their weight. Both of these are problematic because numbers don’t really tell you the size of anything and all plastic is light, but it’s a start. During one of our last beach clean-ups we found a total of 6800 items and based on the numbers 32 percent of that were net cuttings, so very much linked with the fisheries. As plastic breaks down so much we also have lots of unidentifiable pieces. The third most common findings by number were caps and lids and the forth was shotgun cartrages which are most likely local as there is sea bird hunting in this area. If you look at the results based on weight, fishing nets and ropes are the number one find on the beach, followed by floats and buoys.

We also classify brands and nationalities. For example, if you would find a Coca Cola bottle you would try to specify if it’s from Iceland by checking if it has Icelandic import companies on it. We also look for animal bite marks and life growing on plastic like algae or barnacles. Other categories are wood, metal, glass, pottery, ceramics and sanitary waste – and bagged dog feces is even its own category.

What do you do with driftwood when you find it during beach clean-ups?

According to Icelandic laws anything that comes up on shores belongs to the owner of the land. People want to own driftwood but they don’t want to own plastic – so the driftwood stays on the land and the plastic becomes the researchers’. But when you’re doing a beach clean-up you go straight to where the driftwood is because that’s where the big nets are tangled together and where you find the good stuff.

Catherine Chambers

Dr. Catherine Chambers is a senior scientist at the Stefansson Arctic Institute and research manager at the University Centre of the Westfjords. She is PI on the Nordic Cooperation project FINPlast: “Plastic in commercially important fish stocks in Faroes, Iceland, Norway”, co-PI on case studies in the H2020 consortium JUSTNORTH: “Justice and Equity in the Arctic”, vice chair of the Social and Human working group of the International Arctic Science Consortium, vice chair of the University of the Arctic Thematic Network on Ocean Food Systems and serves on the Icelandic Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources working group on Arctic affairs. She was appointed by the Icelandic Chairmanship of the Arctic Council to participate in the development of the Regional Action Plan for Arctic Marine Litter. Her specialties focus on human dimensions of fisheries, ocean governance, human relationships with marine resources, changing coastal communities, fishermen’s knowledge, and small-scale fisheries.