Iceland without ice would be strange

Interview with Halldór Björnsson, Icelandic Meteorological OfficeWhat impacts of climate change can already be observed in Iceland?

In many ways, Iceland is particularly suitable for looking at the impact of climate change on a local level, because it has warmed about three times faster than the global average in the last decades. Warming has slowed down in the past few years, but that is understandable, as Iceland couldn’t possibly warm much faster than the rest of the globe for a very long time – it would end up being the warmest spot on the globe.

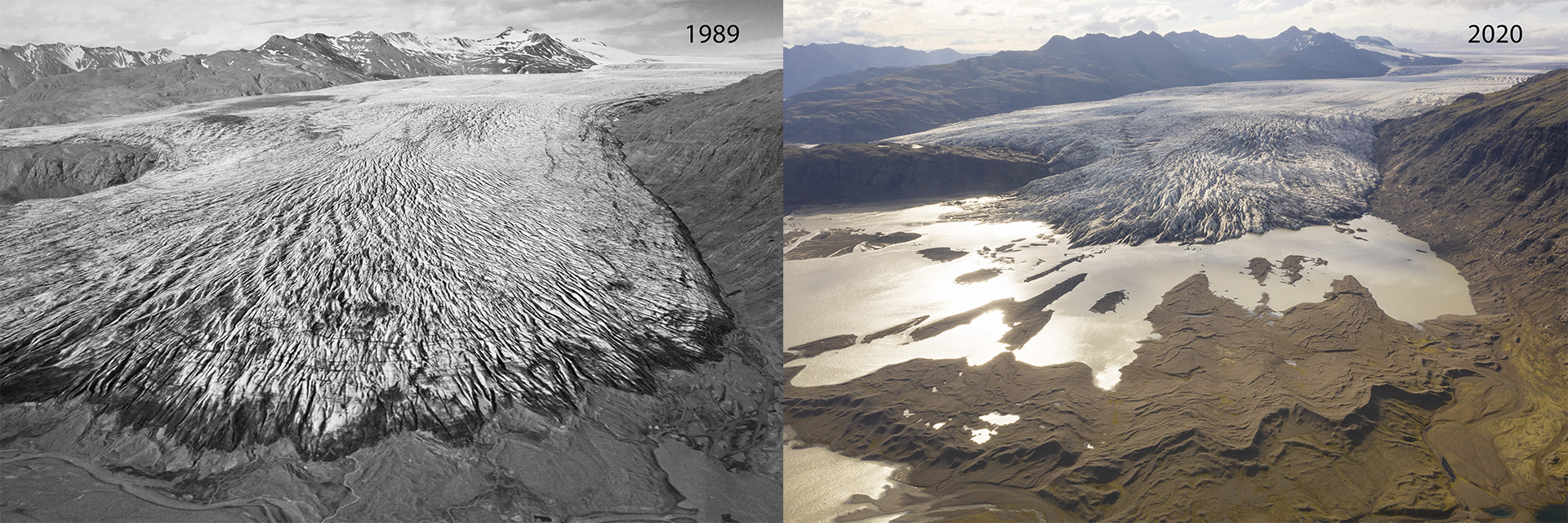

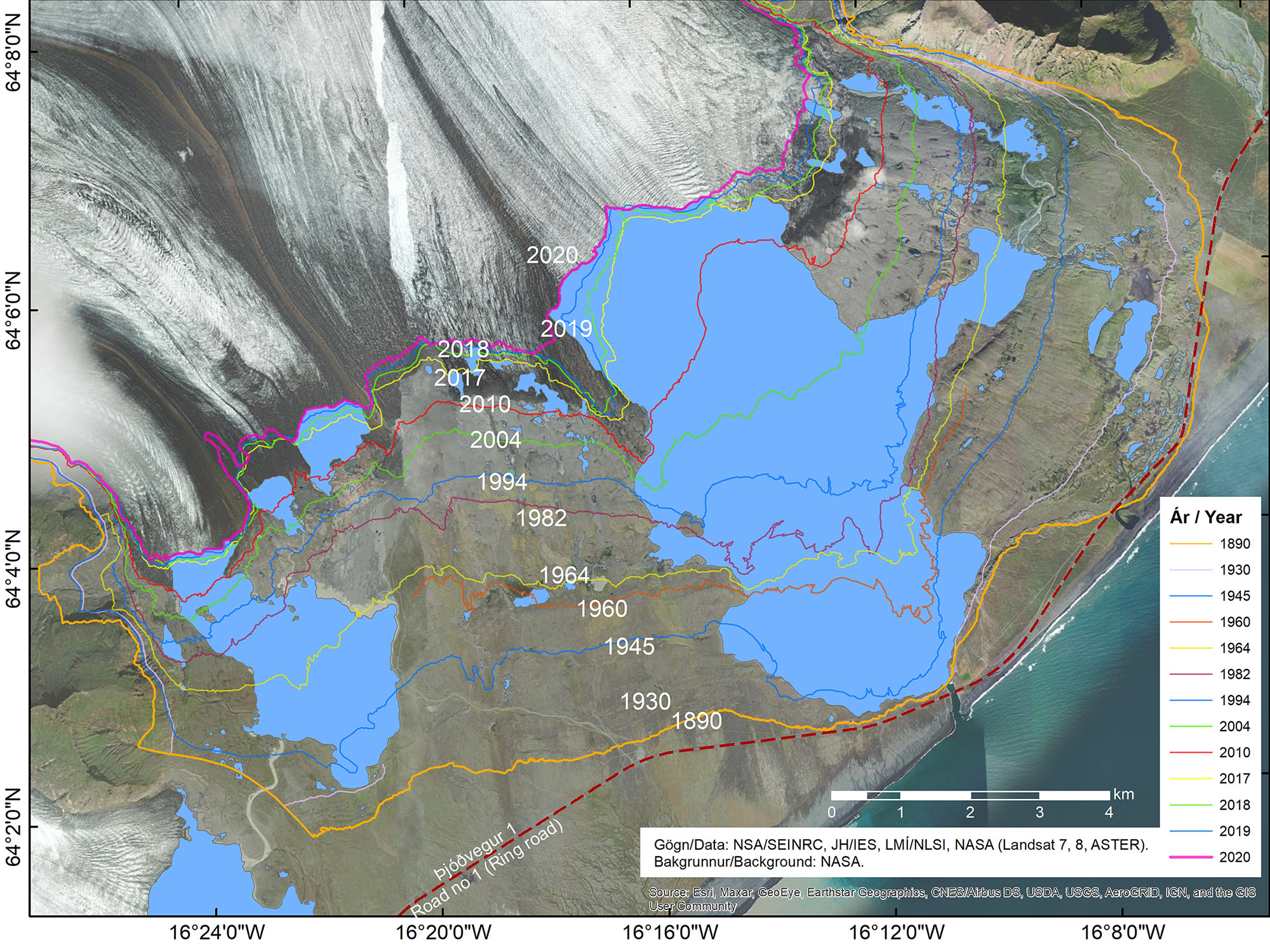

We have seen significant changes as a consequence of a warming period that lasted from the mid 90’s to 2015 – glacier retreat being the most obvious one. Glaciers were advancing until the end of the 19th century, then it warmed up and glaciers started retreating until the mid-century and after that, their mass slightly increased again. As glaciers played a key role for the climate at the time, they were quite vulnerable to warming. So as soon as it began to warm again in the 1990’s, the glaciers started retreating and thinning. A new report shows that glaciers are losing mass almost every year, even though these are glaciers that usually receive a lot of snow in the winter. At the turn of the century, we had about 300 glaciers in Iceland, also counting the small ones. A mapping project in 2017, revealed that 56 had vanished. So we’re losing a lot of the smaller ones. I don’t think that we will see the big glaciers vanishing entirely, even if the snow line rises – because they are very high – but we might lose chunks of the big domes – like Vatnajökull in the long run. An ice cap like Vatnajökull, would eventually break into a few smaller mountain glaciers on the highest mountains.

When glaciers retreat, what happens next?

When glaciers melt there are all sorts of things that happen as a consequence – landslides for instance. This is when a retreating glacier leaves the mountain slope unstable and a landslide results. We’ve had a few of those. Another consequence is that pro glacier lakes – lakes that form in front of glaciers – are growing in numbers. Breiðamerkurlón, the biggest glacier lagoon in south Iceland, didn’t yet exist in the late 19th century. During summer, glacial river runoff will also change. If a glacier retreats that is on top of a volcano, it will take pressure off a balanced system. This can lead to increased lava production – we do have substantial volcanic hazards and this would add to them, but exactly how much more lava would come to the surface in eruptions is unclear.

Melting glaciers also cause land rise as the huge weight of ice is being removed. Depending on how much the glacier melts, the region of Breiðamerkurlón glacier lagoon for instance, might rise by one or even two meters during this century. This is one of the few locations where you can be absolutely certain that you don’t have to worry about sea level rise. But dropping sea level is not a good thing either. Hornafjörður is the nearest town and its harbor at the river delta is threatened. The land there rises by one centimeter per year, one meter per century. The inflow and outflow of tidal waters will be reduced, leading to increased sedimentation of the water array, thus making it more difficult to sail out and in.

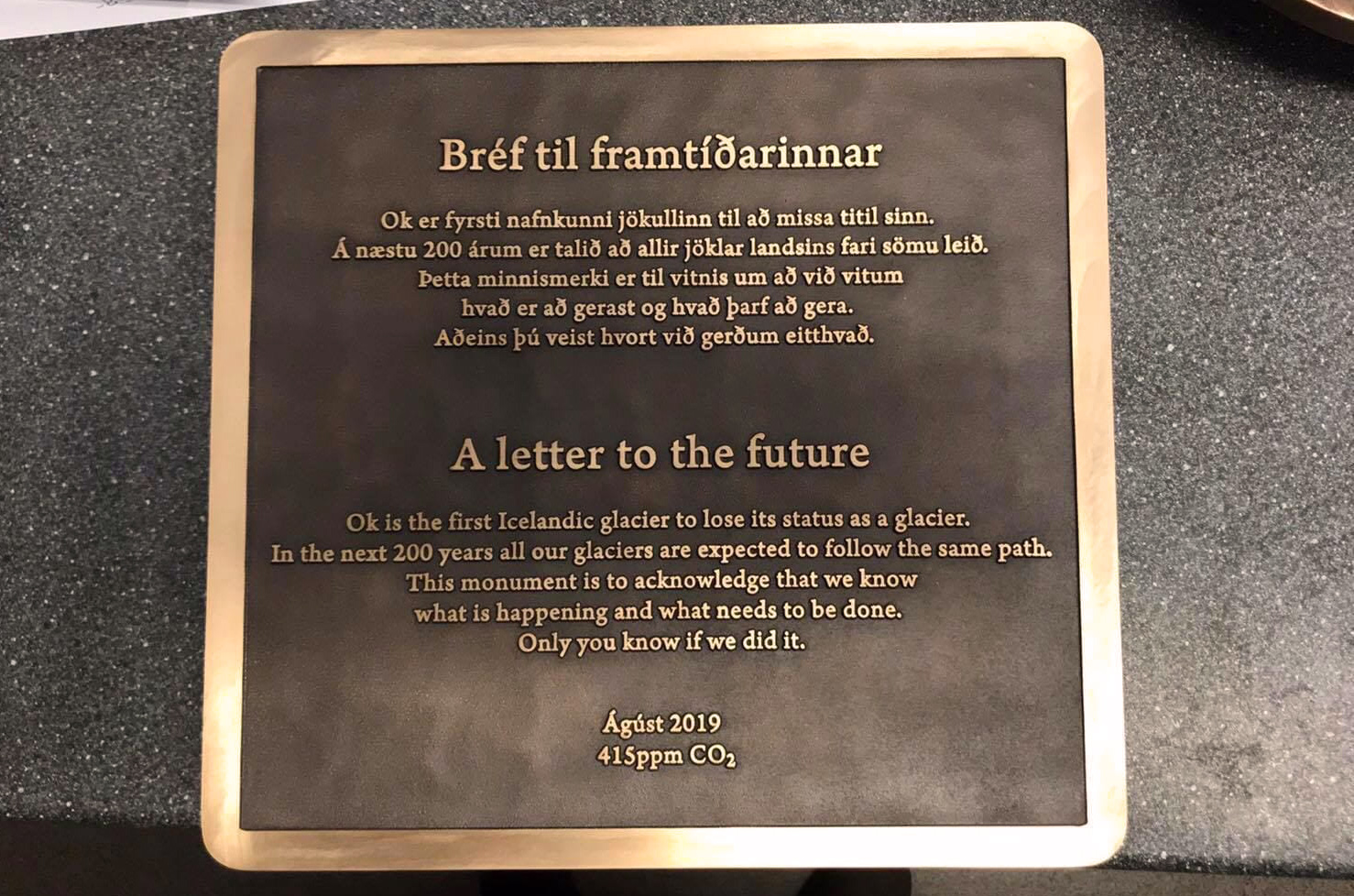

In 2019, Iceland held a funeral ceremony for its loss of the glacier Ok – how do you remember it?

Ok was probably one of those glaciers that were always very sensitive and it couldn’t tolerate much warming. The first time I heard that it would vanish, was in 2004 when one of my colleagues took pictures of it at the end of the melting season and noticed that all the snow from winter was gone. That means the glacier can’t accumulate new snow, even if it gets some next winter, it won’t be enough to offset what has melted away. It’s like a bank account – if you go below zero before you receive your next paycheck, that’s bad news.

A few years later, my colleague noticed that Ok had stagnated. A glacier is an ice mass that is big enough to move under its own weight. Once that weight goes away you have something that is usually referred to as an ice field, which can also vanish eventually. After 2004, Ok transformed into an ice field and by that time it was already very sensitive. A few warm summers were enough to kill it completely. Ok wasn’t the first glacier that died – but the biggest and the most notable one. It didn’t surprise me as I had been witnessing its development for a decade, but I attended the ceremony and I would say, it was a reminder of things to come.

Would you say it had an alarming effect on Icelanders?

After the funeral ceremony, we published pictures of glaciers that we expect to be the next ones to go. Snæfellsjökull, for example, is the only glacier you can see from Reykjavík at the end of the peninsula across the bay. It’s about 40 meters thick where it is thickest and has been losing more than a meter per year. As Snæfellsjökull is pretty high, it will most likely always be a snow-capped mountain. If that glacier would go away, I think people would respond much faster.

But I didn’t really see Icelanders panicking over the loss of Ok. I guess if you explain to them that we already lost 50 glaciers, they assume it’s business as usual. But Iceland without ice would be strange.

What other impacts of climate change are already noticeable?

Iceland has become much greener. A paper that came out in 2011 showed which areas in Iceland have greened. I didn’t know about it until we did a climate impact assessment in 2015 and mapped regions with warming and enhanced precipitation. When I compared the maps, it was astonishing to see that these areas overlapped almost 1:1, so the tie between warm and thus moisty regions and greenery was quite strong. Increased CO2 levels probably also play into it – it’s a bit like adding fertilizer. The greening of Iceland is by most people here considered a positive thing and we are hopeful that we’ll be able to turn back the clock on deforestation.

We also have a lot of new types of birds, probably due to changes in our landscape – once you have more forests, they can host birds that nest in trees and wouldn’t have come to Iceland otherwise. But it’s not all positive, we also have sea birds emigrating to other regions further north because Iceland has become too warm for them.

Warming in the ocean has also impacted fish populations – we have seen 26 new types of fish in Icelandic waters in recent years, including commercially important ones like mackerel, which has only been found here during warm periods. Mackerel numbers started to increase in 2008. They became quite massive in the following years and we immediately got into a dispute on quotas. A warmer ocean led to changes in fish population which then led to a changing political arena. People argued that the dispute between Iceland and the EU over the fishing rights for the mackerel, delayed our application for the EU. Eventually, the new government had no interest in joining the EU. I’m not going to claim that our EU application was scuttled due to global warming, but the connections are interesting.

Does climate change increase the risk of landslides?

We have landslides caused by receding glaciers, landslides caused by destabilization due to melting permafrost and a third category that is fairly new to us. There are regions that tended to get lots of snow in the winter. Now that it’s warmer, part of the snow falls as rain and we’ve had cases where the rainfalls destabilized the soil and caused landslides – this is certainly something to worry about.

What are your predictions for the future?

Climate in Iceland is very much governed by what happens in the North Atlantic region. The reduction in sea ice has led to substantial warming in the ocean north of Iceland and we would expect this development to continue. But there’s something going on south of Greenland – we refer to this region as the cold pool. While the whole globe is warming, there are a few locations, including this one, that don’t. In this case it’s unclear if the cooling is caused by processes in Greenland and melting ice that is freshening the Atlantic. If that’s what’s happening, you would expect the cold pool to settle in and possibly grow in size, which could stall warming in Iceland.

Our climate records go back more than 200 years and they show that climate in Iceland is quite variable on a scale of 30 to 50 years. But once you get into longer time periods, it tends to follow the trend of the rest of the northern hemisphere. Part of the problem is that we don’t know if the old statistics still apply, because we’ve been messing with the system so much. For instance, the rapidly retreating sea ice has a massive impact on the region. We expect climate in Iceland to become even more variable in the next decades but the overall trend should be warming. Even if the cold pool south of Greenland may stall warming for some time, it is unlikely to generate an extended cold period.

Icelandic ecosystems are really fragile – how will they be affected?

Ecosystems change a lot and it’s very hard to conduct controlled experiments. One experiment took place in the mountains close to Hveragerði near Reykjavík. There are many geothermal areas and fairly warm running waters. They put in pipes and changed the drainage, heating up one region and cooling another. Slight warming usually turned out to be beneficial, but too much warming caused the ecosystem to collapse, so that’s clearly worrying.

Sea birds in Iceland have diminished a lot, which is definitely related to environmental changes in the ocean. Warming and acidification have to do with it, but it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact reasons. I recently spoke to a puffin expert who said part of the problem is that the krill that used to live close to Vestmannaeyjar islands, has moved further away. To find food, puffins have to fly two or three times longer than they used to, so they have far less energy for their young and it’s harder to bring back food for them. But if this is a new reality of just a temporary setback, it remains to be seen. This summer has been unusually good for puffins.

There are massive changes ongoing, some of them are connected to environmental change, some to global or local warming. Often in science, the honest answer is that we don’t really know what’s going on. In this case, the lack of knowledge about changes in ecosystems is quite obvious, we do know a lot more about changes in glaciers for instance, because they are much simpler systems.

Over the past decades, Iceland has experienced a significant decrease in the amount of driftwood it receives, a development which is also related to climate change – do you have a favorite driftwood story you want to share?

My grandfather grew up in the northwest of Iceland. Many years ago, probably in the sixties, he was in Isafjörður and found this massive piece of driftwood. He put it into a room at the fish factory, probably the one they used for power generation. It was huge and must have been in the way. He went home to Reykjavík and totally forgot about it. A decade later, someone asked him if the driftwood was his and reminded him that he originally had planned on doing something with it. So my grandfather took it to Rekyjavík, cut a disc from it and had it cleaned. It was supposed to be the top for a table but he still needed a base and he wanted a wooden one. There weren’t any big trees in Iceland back then, except for one big tree that got shipped in from Norway every year – it was the official Christmas tree for downtown Reykjavík. He asked if he could get a part of the tree, had someone cut it up and turned it into the table base. We still have that table at our family cottage – it’s a beautiful piece of work, you can see all the tree rings.

Halldór Björnsson

Halldór Björnsson is a climate scientist at the Icelandic Meteorological Office. His recent research has focused on climate change impacts in Iceland, such as extreme weather and flooding. He chairs the Climate Impact Assessment for Iceland, a project that reports on the state of knowledge about observed and projected climate change in Iceland, its impacts and consequences.

Picture credits:

Snæfellsjökull (Header image), Kollektiv Lichtung

Fláajökull 1989 & 2020, Changes in the ice margin of Breiðamerkurjökull outlet glacier by Jökulsárlón lagoon since the end of the 19th century published in the newsletter “Overview of Icelandic glaciers at the end of 2020” by the Icelandic Meteorological Office, CC-BY 4.0

Plaque at the OK monument, Photo: Rice University, CC BY-SA 4.0

Large landslide fell in Fagraskógarfjall mountain in Hítardalur valley, West Iceland, 2018, Shutterstock

Puffin, Shutterstock

Driftwood Table by Halldór Björnsson’s grandfather, picture by Halldór Björnsson

Pictures of Halldór Björnsson by Unicorn Riot, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US