Could you tell us a little bit about your relation with driftwood?

I grew up with driftwood. My parents resettled here when I was a baby, they rented a part of the Árnes farmland and built the farm Árnes 2. Thus, we own half of the benefits that used to belong to Árnes. Quite a lot of the driftwood was used, all farmhouses were built from it. I don’t remember the old driftwood practices, but my dad used to saw down the boards with a small hand saw and then planed it by hand to build interiors of the house.

Was it your father who inspired you to study construction and carving?

When he had a free moment at night, he would often carve animals for us children with a knife. I was really fascinated by it, so this might indeed have been the beginning. After finishing elementary school, I went on to study bookbinding and carpentry in Reykjavík. In 1982, after having lived in Reykjavik for 14 years, I moved back north and have been here ever since.

Has the amount of driftwood that washes ashore your beach, changed over the years?

The biggest driftwood arrival I remember was in 1966. The winter was very cold and there was a lot of sea ice that brought an enormous amount of wood. There have always been big variations in the amount of driftwood we receive. But for the past 8 years, it’s been decreasing gradually. The past two winters have barely driven a few logs ashore. This winter, it was only a single log.

My theory is, that oceanic currents might have changed or less wood gets lost during timber logging in Siberia. Climate change is another reason because driftwood needs sea ice to travel. Driftwood used to get melted out from the sea ice east of Jan Mayen and then transported with the East Greenland Current Gulf Stream to Iceland. But as there’s less and less sea ice, driftwood either doesn’t get frozen inside it in the first place, or melts out elsewhere, further east or north. If driftwood is just loose in the ocean, it can’t float that far.

How can you tell if you can utilize the driftwood?

I learned it from the old men who were working driftwood. The main product was fence posts and after sawing a piece of wood apart, you can see very quickly if it’s usable. A log might look really good from the outside, although it’s rotten in the center; in this case you can only use it for firewood. I built this museum here completely out of driftwood using a band saw. I would guess that about 40 percent of the driftwood we get is usable in proper buildings.

What are the most important things you learned from the old men?

They taught me to recognize the tree species – also by smell – and how to differentiate between good and bad wood. You can for example, check the wood’s density with a hammer. You take a small sledgehammer, knock on the end of the log and you hear by the sound whether the wood is tight, soft or somewhere in between.

I also learned from them to judge whether the log should be sawed from the top or the root. If you’re using a wheel saw and the tree narrows up, you saw into the wider end first, otherwise the wood tends to get stuck and clamps together. You never know if the driftwood you find has landed on other beaches before and washed back into the ocean. That‘s why there’s so much sand and rocks in the surface of the wood. If you’re going to saw it with a band saw, you have to peel quite a bit off to get rid of sand and rocks, otherwise it will destroy the saw blades.

You mentioned earlier that you own a driftwood boat?

My dad bought this boat around 1945, from the boatbuilders north of here in Reykjafjörður. It’s always been maintained with driftwood and we still use it to sail the islands here. The builders used certain shapes of nods and timber, so the boat would be less likely to break. The front and back woods are twisted with steam to fasten them. I think it’s mostly pine, except for the banks. Larch splits too much and spruce is a little rougher and not as durable as pine. If a boat was built of spruce with knots in it and it would dry up, the knots would just pop out and the boat would leak.

The people of Strandir and Húnavatnssýsla used to be involved in a quite lively exchange.

I don’t really know how far back this exchange goes. The people of Strandir made craft items like tools and utensils from driftwood. They transported them by boats, sometimes they would also drag logs of driftwood over Húnaflói to Húnavatnssýsla, even all the way to Skagaströnd, Blönduós and Hvammstangi. They traded their driftwood items and logs for hooks, fishing lines and other things that were not available in the stores here. The last voyage of this kind happened in 1915, when the old shark ship in Ófeigsfjörður was loaded with driftwood and towed to the Skagi Peninsula by another boat. I assume the barter system stopped after that, because more stores opened in Strandir and people could buy what they needed right here.

But there are also centuries-old stories about craft driftwood items from Strandir, being transported south to Þingvellir and sold there. A man called Stókeralda (large container) Jörundur used to live here – he received this nickname because he carried large containers on his back to different parts of the country.

Do you have a favorite driftwood story?

I once made a driftwood trip north on the Hornstrandir coast to the deserted lands. We filled three boats with driftwood and even pulled more logs by boat. It was enough for three thousand driftwood fence poles. It’s the most fun experience I remember. Otherwise, I really like to walk on the beaches, I’m kind of a “fjörulalli” (fjörulalli refers to a folklore creature that sometimes appeared on beaches) and always find something.

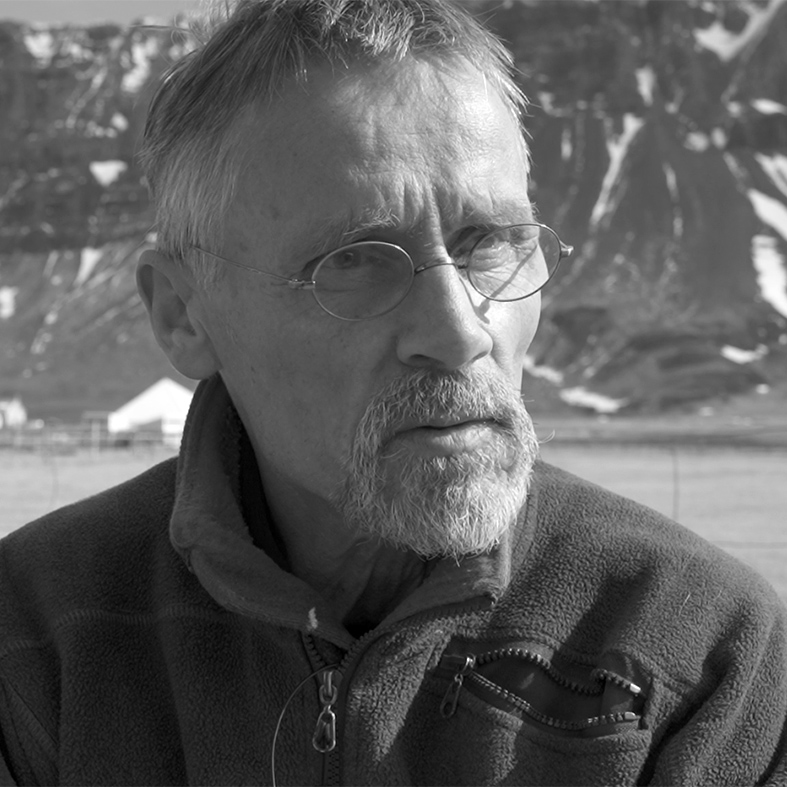

Valgeir Benediktsson

Valgeir Benediktsson was born in Reykjavik and lives as a carpenter and craftsman in Árnes in the Westfjörds. He built and runs the local museum “Minja- og handverkshúsið Kört”. The exhibition includes historical objects from the Strandir region as well as Valgeir’s own handcrafted objects.