Driftwood plays a very important role in Iceland’s history. How have people made use of driftwood as a natural resource?

Due to the lack of trees, finding fuel and building material has been a crucial problem ever since the settlement. Older sources indicate Iceland had indeed woodlands “from mountain to sea”. These were probably birch and willow forests, that became very scarce when the settlers cut down and burned the woodlands for agriculture and husbandry. Additionally, the Little Ice Age led to a much harsher environment. But the settlers could rely on driftwood that was piling up at the beaches at the time. Throughout Iceland’s history, driftwood farms spread across its Northern and Western shores and parts of the East. As the inner wooden structure of turf houses as well as many household items were often made of driftwood, these farms were quite wealthy. In areas such as Strandir in the Westfjords, the locals were very skilled craftsmen and as Sturlunga saga describes, they travelled the country and sold household items made from driftwood. Craftsmanship was attributed with magic and magical skills and in folklore the two often meet.

But even before the settlement of Iceland, driftwood played a role in the world view of the North. One example is the origin story of Snorri’s prose Edda: when Odin and his brothers walk along the beach, they come across two logs of driftwood. They breathe life into them, thus creating Askr and Embla, the first man and woman. It’s interesting to compare that narrative to the Bible where Adam was formed from clay – which was an important natural resource in the Middle East. But unlike Eve, Embla was not made from Askr’s rib but from another driftwood log. So one could state that driftwood is a source of the Divine.

According to Landnámabók (Book of Settlements), the settlers would throw their high seat pillars that once adorned the thrones of their old farmsteads overboard – and their pagan gods would use the currents to guide them to fertile lands, where they build their farms. Another example from the sagas, is that a settler whom made a particularly good sacrifice towards Thor, would be rewarded with a great boulder washing ashore that he could make use of in various ways. So in that way, currents are also a divine language, a way of gods speaking to humans.

How is driftwood used today?

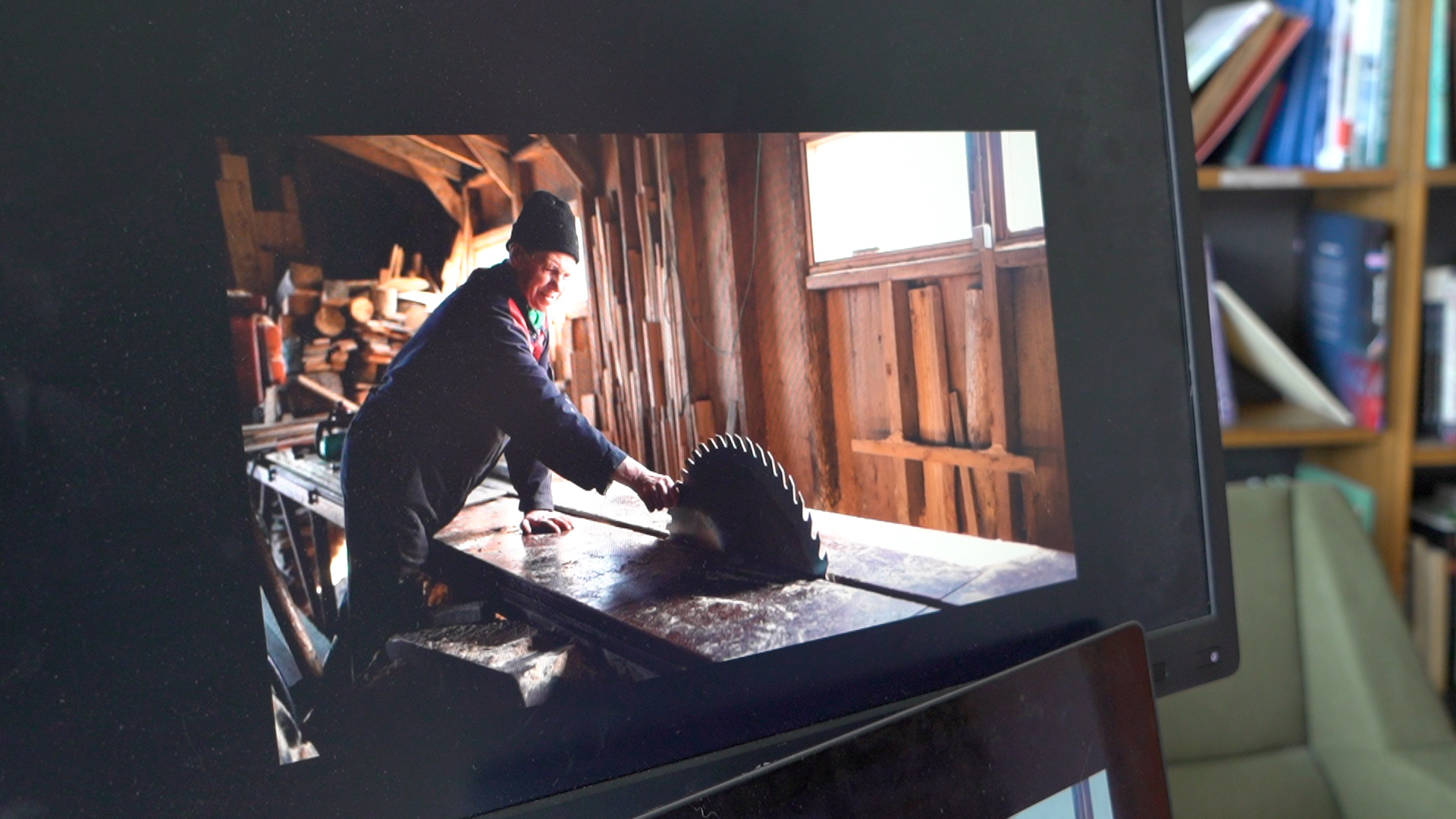

Driftwood farmers mostly make use of their driftwood themselves, but sometimes farmers also pool together to buy a sawmill and distribute driftwood lumber to other places. In many areas where there is a great deal of it, like Strandir in the Westfjords, or Skagi in the Northwest, driftwood is still used as a building material for houses. And it’s widely used for fence poles. For a long time the fence pole was also an excellent indicator for prices and inflation; like the Big Mac Index is in today’s economic world. Since the economic crash, we don’t have McDonald’s in Iceland anymore, but we still have the fence pole that can tell us a little bit about the development of our economy. Having said that, plastic fence poles are becoming more common than driftwood fence poles these days. They are more weatherproof and the animals don’t eat them or use them as scratching poles. Driftwood is also used in landscaping and can be a part of gardening decoration – you might even find a carved high seat pillar!

What about the legal history – who used to own the driftwood and how has that changed?

There were quite complicated laws concerning the ownership of driftwood. The most basic law states that the owner of the farmland owned the driftwood that washed ashore. But the shore is an ever changing arena – so the farmers had their own driftwood markings to make sure they could recollect their wood in case it drifted off their shore again. Over a long period of time, the law also stated that anything manmade belonged to the King of Denmark, Iceland and Greenland. There were a lot of legal fights for example, on whether a piece of driftwood was shaped by natural erosion or used to be part of a boat which in the latter case, would lead to severe punishments for the farmers.

It was also common for the church to own shares of driftwood farms that they would come to collect. There are even various narratives of greedy priests whom would visit old farmers at their death bed, laying their ear at their lips, pressuring them to give up shares of driftwood to the church with their dying breath – and then the priest would say “Oh, this darling keeps giving and giving.”

How would you describe the relation between the usage of driftwood as a natural resource and as a part of storytelling – are these two sides of a coin?

I think narratives and phenomenological reality are very intertwined, especially through the centuries. You will see cases where it’s very difficult to detract one from the other. For example, there would be folklore beliefs about what kind of driftwood you may use for boat building. If the wood falls in a certain way, it would cause the boat to drown, so people didn’t use it.

Driftwood also has to be looked at in the context of its surrounding, the natural environment. What kind of cultural space is the beach? It’s an arena where driftwood, whales or other goods wash ashore but also corpses and mines from World War II. And of course there’s narratives of poisonous and monstrous things creeping and crawling in the dark. The environment is a force field that brings driftwood to the settlers. But it’s also a transarctic arena that connects the people of the rivers Yenisey and Lena in Siberia, Northern Russia, and the population of Iceland in this amazing way where neither knows of the other.

Would you say driftwood is a sort of messenger?

Yes, you could look at it as a messenger or as a quite significant non-human actor in people’s lives and culture. It almost has its own agency – ice sheets help to bring it to the Transpolar Current, which then brings it to Iceland, Greenland, Svalbard or even Baffin Bay on the Northwest coast of Greenland. In the minds of the settlers, currents were a divine language but they continue to be a very significant force in the life and culture of Icelanders.

What role does driftwood play in creating the image of the North?

“Half of the fatherland is the sea,” is an old saying. I think driftwood plays a strong role in creating an image of the North, but one that is very often overshadowed by other factors such as polar bears or receding ice. There are also indications that the ‘driftwood delivery’ to Iceland is decreasing. When you talk to farmers who own driftwood beaches you will hear various theories – whether it’s a direct effect of climate change, a change in transporting lumber from river logging to trucks or oil price fluctuations. Farmers already feel the lack of driftwood and are concerned. Although driftwood has lost its importance due to increased import of wood, it is a loss both aesthetically but also as a resource. So you see a transarctic discourse taking place in modern times where climate change figures in very strongly.

We talked about things that wash upon the beach – what about the other direction, what kind of things wash from the land into the sea?

Looking at what we put into the sea is a very contemporary issue and one that is growing in importance as Iceland becomes more industrialized. In that way we are connected to the great challenges that we face globally. “Long will the sea receive,” is an old saying. Whether it’s emissions, acid rain or goods from sunken ships. The sea remembers everything. It’s a question of growing concern and perhaps an instigator of frustration amongst Icelanders: How do we use the beach? As a natural reserve or the backyard of the fishing and aluminum industry?

Kristinn Schram

Kristinn Schram is associate professor of Folkloristics/Ethnology at the University of Iceland. His field of study ranges from oral narrative, festival and ironic performances to media representations, in a variety of cultural spaces such as Arctic shores and city streets. He lectures on the dynamics of identity, national images and tradition, folk narrative and urban folklore. Among current research topics are the exoticism of the north, transnational performances of the ‘West-Nordic region’ and sociocultural aspects of climate change and mobility in the North Atlantic.